IN SEARCH OF...

THE SEPTEMBER 1913 LINCOLN HIGHWAY IN OHIO

Galion to Lima

Michael G. Buettner

July 2005

In September 1928, the Lincoln Highway Association completed their marking of

the final version of the route across Ohio, setting a total of 241 concrete

posts along 242 miles of brick, concrete, macadam, stone, and earth. This final

route was

remarkably

different than the original route proclaimed fifteen years earlier—not just in

the improvement of its surfaces, but also in its orientation. Considering the

original routes through Ashland, Galion, Marion, Kenton, and Lima—plus other

variations in the years between 1913 and 1928—at least another 242 bypassed

miles of Lincoln Highway alignments can be included as part of Ohio's

transportation history. Thus, for every mile of 1928 alignment that was marked

in Ohio, there was one mile of pre-1928 alignment that was bypassed.

remarkably

different than the original route proclaimed fifteen years earlier—not just in

the improvement of its surfaces, but also in its orientation. Considering the

original routes through Ashland, Galion, Marion, Kenton, and Lima—plus other

variations in the years between 1913 and 1928—at least another 242 bypassed

miles of Lincoln Highway alignments can be included as part of Ohio's

transportation history. Thus, for every mile of 1928 alignment that was marked

in Ohio, there was one mile of pre-1928 alignment that was bypassed.

This newly-prepared "Map of Proclaimed Route of Lincoln Highway/September 1913" is drawn in the classic style of the early strip maps of the Automobile Club of Southern California. Images with blue borders are expandable.

Most of those bypassed miles have been charted in the research project entitled A History and Road Guide of the Lincoln Highway in Ohio, which was first published by this author ten years ago. However, sixty of those bypassed miles were part of a short-lived segment of the transcontinental route which passed through Marion and Kenton for just three weeks in September 1913. Given that this part of the highway apparently existed only on paper, and was likely never marked with any Lincoln Highway signs, the road guide author never saw the need to chart that particular alignment.

Recent events, though, require a change of thought. Successful promotions by the

Ohio Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor

have inspired folks in Kenton and Hardin County to rediscover their highway

heritage in refreshing new ways. For example, the idea of the Lincoln Highway

Buy-Way Yard Sale came from Charles Brunkhart of Forest, a Hardin County town

which hosted the route for six years after the Kenton alignment was erased. Also

of significance is the fact that the National Park Service, in their recent

study of Lincoln Highway "special resources," has inventoried several sites

along this first route.

Thus, the

time has come for this author to explore the originally proclaimed 1913 route of

the Lincoln Highway—a route which came to be known as the Marion Way, then the

Harding Highway, U.S. 30-South, and now State Route 309.

Thus, the

time has come for this author to explore the originally proclaimed 1913 route of

the Lincoln Highway—a route which came to be known as the Marion Way, then the

Harding Highway, U.S. 30-South, and now State Route 309.

According to Rand McNally's Official 1926 Auto Road Map of

Ohio, the signs for the Harding Highway featured a black sylized Roman letter H

within a black circle, all on a white diamond.

Let us begin our journey in Galion, which in 1913 was the first major city west

of Mansfield. Galion held its location on the Lincoln Highway until 1921, when

the route between Mansfield and Bucyrus was revised to pass through Crestline

and Leesville. Galion—along with Marion, Kenton, and Lima—was a key commercial

point on Main Market Route No. 3, which connected these and other western

locations with county seats in the eastern half of the state. When Lincoln

Highway fathers

proclaimed

the route in September 1913, the market route provided a ready-made link in the

chain that was the transcontinental highway, and thus would have seemed a

justifiable choice.

Dedicated in 1900, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974, the Big Four Depot in Galion is the point of beginning for this tour.

However, at the end of that same month, Henry Joy made a significant revision. For whatever reason, sixty miles of the market route were abandoned in favor of a path which was supposedly shorter, bearing westerly from Galion to Bucyrus before continuing on to Upper Sandusky and Lima. Actually, Joy had made the path to Lima longer by three miles, with a series of tedious right angle turns and dangerous railroad grade crossings being the rule, and not the exception, west of Bucyrus. This author remains steadfast in his belief that politics—not mileage—provided the impetus for the sudden change. These matters, which included key players such as Lincoln Highway Consul John Hopley (from Bucyrus) and Governor Frank Willis (from Ada), are discussed in detail in a Spring 1997 article in The Lincoln Highway Forum, entitled "Before the Route Was Straight: Ohio's Zigzag Route."

A good place to zero the trip meter in Galion is at the Big Four Depot, the impressive facility at the first railroad crossing east of the "Historic Uptowne," or three blocks east of the town square. The depot was dedicated in 1900, and served as the division headquarters for the Cleveland, Chicago, Cincinnati, and St. Louis Railroad, commonly known as the Big Four. Look for the C.C.C.&St.L. letters cut in the west face of the building. Also take time to read the Ohio Historical Society marker on the site, which was placed as part of the same Ohio Bicentennial Commission program that awarded the Ohio Lincoln Highway League their marker at Upper Sandusky.

From this point, bear west through town on Harding Way. The city's main east-west street was originally platted as Main Street, but the city fathers changed the name to Lincoln Way at the coming of the transcontinental highway. The name change to Harding Way was probably made some time after the route was realigned through Crestline in 1921, or perhaps shortly after the death of President Warren G. Harding in 1923. As our journey continues west, the significance of the Harding name will be easily understood.

A concrete post replica was placed at the southwest corner of the town square in

September 2004. Although the nearest concrete post erected in 1928 would have

been just up the road in Leesville, this replica is a splendid reminder to the

community

of their Lincoln Highway heritage. The newly renovated Lincoln Way Professional

Building, on the

northwest corner of the square, reinforces that same idea.

community

of their Lincoln Highway heritage. The newly renovated Lincoln Way Professional

Building, on the

northwest corner of the square, reinforces that same idea.

This concrete post replica on Harding Way is a reminder of Galion's place on the Lincoln Highway from 1913 to 1921.

Just west of the square is the restored Galion Theater—with its fine marquee—which now hosts events such as the recent landmark meeting of the Ohio Lincoln Highway Heritage Corridor. This gathering, which included the dedication of the nearby replica post, introduced many new businesses and visitors bureaus from across the state to the potential of the highway as a linear tourist destination.

At the one mile mark, turn left on Portland Way—which traces the Portland (now

Sandusky) and Columbus State Road from pioneer days—also following the signs for

State Route 309. This numerical designation will be followed all the way to

Lima, except for those places where the author has charted some interesting

remnants of the September 1913 alignment.

The relative quality of this route—in comparison to the later routes of the

Lincoln Highway—is borne out by the fact that this alignment became the original

path of U.S. 30 when the federal system of highways was first designated in

1926. However, politics came into play again, and in 1931, this segment became

30-South, and the traditional Lincoln Highway route was labeled 30-North. By

1973, the 30-North corridor had been improved with the construction of several

intermittent bypasses and four-lane sections, and had once and for all surpassed

the southern route as the route of choice for through traffic. It was then that

the "cumbersome compromise" of north and south numbers was finally dropped in

favor of the simpler U.S. Route 30 and State Route 309 numbering, respectively.

At 2.0 miles, State Route 309 crosses two sets of railroad tracks. Although both tracks are now the property of CSX Transportation (by way of Conrail), these tracks were previously the competing lines of the Big Four and the Erie Railroad. The railroads ran side-by-side for all of the twenty miles between Galion and Marion, making plausible here the legendary stories of one engineer racing the opposing train from one city to the other.

At 4.6 miles, State Route 309 begins a sweeping curve to the right on a new alignment opened in about 1970. The previous version of State Route 309, and the alignment used in 1913, is now obliterated by a modernized State Route 61 for the short distance to its junction with State Route 288. At the southwest corner of this four way stop, an old road remnant survives through the trees, along with an old bridge. The structure is solid enough to walk on, but most of the bridge rails have disappeared, and the few pieces which do remain have rusty rods exposed in crumbling concrete. With the vegetation heavy, highway archaeologists will find this a challenging photo subject. To return to State Route 309, follow a modernized version of State Route 288 a short distance to its western terminus, and then turn left.

At 6.3 miles, State Route 309 passes through the unincorporated town of Iberia. This was once the home of Ohio Central College, where at age fourteen, Warren G. Harding began his secondary schooling. He was considered a popular student—editing the yearbook, playing a horn, and entering speaking contests. Harding graduated in 1892, just a short time before the academy burned to the ground. Had it not been for Harding's time there, the school would likely be forgotten—after the fire, it was never rebuilt.

At 9.0 miles, turn right to follow one mile of an old road alignment that is now

designated Marion Galion Road. Half a mile beyond the turn are the remains of an

ancient railroad viaduct that was indicated on a 1915 map drawn by Marion

interests to promote their route. One of the selling points of the Marion Way

was that it had five less grade crossings than the competing

Lincoln

Highway route, which was derided as "a narrow, crooked lane...through

swampland."

Lincoln

Highway route, which was derided as "a narrow, crooked lane...through

swampland."

On the old Marion‑Galion Road near Iberia are the abutment walls of an old railroad viaduct under which the original Lincoln Highway route would have passed.

The viaduct was the property of Toledo and Ohio Central Railroad, one of the

weak sisters in the New York Central system of lines that also included the more

prominent Big Four. It was therefore one of the first lines to have its tracks

pulled up when the railroad industry was in a major decline. Interestingly,

Warren G. Harding worked on a crew that laid the first tracks down. The narrow

opening and hazardous dip at the viaduct eventually proved insufficient for the

increasing traffic on U.S. 30 South, and a new grade separation was built just

south of here on the present alignment of State Route 309. Continue west for

another half mile and rejoin State Route 309 after turning right.

At 12.5 miles, watch for a tall communications tower on the right side of the

road, and again leave the state highway by turning right. Because this old road

remnant is in Morrow County and not Marion County, it carries a designation

inconsistent with other similar remnants—Canaan Township Road 39. Follow this

road through some tight curves into the picturesque village of Caledonia, where

the road becomes Marion Street, and find a place to park your car in the

surprisingly spacious town square. Each quadrant of the square has a point of

interest, with plenty of photo opportunities for those with various highway

interests. The impressive town hall and a modest business block are on the

northeast quadrant, a war memorial and historical marker are on the northwest

quadrant, and an old canopy gas station survives as an insurance office on the

southwest quadrant. I missed it on my trip here, but Mike Hocker of Galion tells

me that there is a fine local meat market on the southeast quadrant. In the

excitement

of my day-long journey, I had skipped lunch, and could have enjoyed at least a

stick of good beef jerky while I was stopped.

excitement

of my day-long journey, I had skipped lunch, and could have enjoyed at least a

stick of good beef jerky while I was stopped.

An old canopy gas station on the photogenic town square in Caledonia is now home to an insurance business.

One thing that I did not miss during my short visit to Caledonia was the earthshaking arrival of a fast freight train immediately north of the square. As I exited my vehicle and planted my foot on the ground—just in time to hear and feel the approaching train—I was reminded of a similar event during my first visit to western Nebraska. The surreal experience was complete when I looked up to see two freshly painted Union Pacific engines leading a long consist of container cars, blasting through the shockingly gateless crossing (flashers only) at 60 miles per hour. Although most engines passing through here would be in the livery of CSX, it is not unusual for contemporary railroads to do a run through with foreign engines from the West.

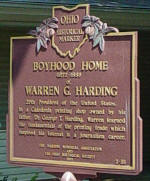

Just one block south of the square, on the northwest corner of Main Street and

South Street, is the boyhood home of Warren G. Harding. The adjacent historical

marker explains that it was in a Caledonia printing shop owned by his father

that Harding

"learned

the fundamentals of the printing trade which inspired his interest in a

journalism career." Warren also participated in the town band, playing the alto

horn—an instrument he continued to play in future years in Marion.

"learned

the fundamentals of the printing trade which inspired his interest in a

journalism career." Warren also participated in the town band, playing the alto

horn—an instrument he continued to play in future years in Marion.

The boyhood home of Warren G. Harding is on Main Street, one block south of the town square, in Caledonia.

Given the several possible diversions in Caledonia, it would be wise to return to the town square long enough to reset your trip meter to zero. Then go south on Main Street four blocks past the Harding home before turning right onto a curving portion of State Route 309. When it was still U.S. 30 South, a two lane bypass was built around Caledonia in the 1950s. A very short old road remnant, now designated Section Line Road, is colinear with the east west portion of the improved highway.

At 2.7 miles, veer right from the state highway onto another road remnant designated as Marion Galion Road. Just before reaching the railroad, veer left and follow one mile of narrow unpainted pavement that parallels the tracks. According to the Claridon Prairie historical marker near the west end of the road, the grassland between the pavement and the railroad "is one of the few surviving remnants of the once extensive prairies that were part of pioneer Marion County." The strip was "preserved by chance when the railway and road were constructed side by side" and "contains more than 75 species of significant prairie grasses and flowers." The sunny afternoon of my visit was certainly made brighter by walking among the orange day lilies that were out in full force.

After passing the historical marker, turn left at the stop sign onto State Route

98, then right at the traffic signal to resume west on State Route 309. The

immense former site of the Marion Engineer Depot stretches for two miles along

the south side of the highway. According to yet another historical marker,

during World War II "food, munitions, equipment, and other military supplies

flowed in and out of MED and heavy machinery was renovated." Government

operations were discontinued in 1961, and after languishing for years with

either occasional users or no users at all, the site was renovated in 2003 to

serve in its present role as a distribution, storage, and manufacturing complex.

For now, you may ignore your trip meter and simply continue west into Marion.

State Route 309 serves as more of a back door to the city than it does a front

door. Most of the city's strip malls and hamburger joints are on State Route 95,

just one interchange south on U.S. Route 23, but the splendid new Harding High

School is along this stretch. Within the city limits, the route will also be

signed as Center Street. Westbound tourists following the original 1913 route

will be able to stay on Center Street all the way through the city—including

about one mile that is one way westbound. Eastbound travelers have to follow

Church Street (one way the other way) to make their way through town. Both

streets are wide and well maintained, and the newly attractive downtown seems

very much in contrast to the Rust Belt image often attached to once major

industrial cities such as Marion and Lima.

Upon your arrival in Marion, the hour long tour of the restored Harding Home at 380 Mount Vernon Street is strongly recommended (visit www.ohiohistory.org for hours and other information). It was here that Harding conducted his famous "front porch" campaign, which played a great part in his unprecedented landslide victory in the 1920 election. Ironically, two former newspapermen from Ohio ran for the presidency that year—Harding, who had purchased the Marion Star after honing his skills in Caledonia; and Governor James M. Cox, who had ties to a major newspaper in Dayton. Harding—now an Ohio senator—was popular with the press, and had the foresight to build a Sears catalog home at the back of his neighbor's property. From there, correspondents would regularly prepare their news stories during the spirited campaign. The press house is now operated by the Ohio Historical Society as a visitors center for the Harding Home.

Unfortunately, the presidency of Warren G. Harding is now recalled mostly for

its scandals and corruption. The twenty-ninth president was spared most of the

pain of those revelations, dying on August 2, 1923 while on a speaking tour in

California. Doctors originally cited food poisoning or apoplexy as probable

causes of death, but modern medicine strongly supports that his death was the result of a heart attack—something that was little understood

in that day. Harding died a popular president and was mourned deeply, and the

tomb on the south side of Marion (along State Route 423) is one of the most

impressive memorials anywhere outside of Washington, D.C. The circular monument

of white Georgia marble, with simple Doric features and spacious grounds,

combine to make it another worthwhile diversion while in Marion.

his death was the result of a heart attack—something that was little understood

in that day. Harding died a popular president and was mourned deeply, and the

tomb on the south side of Marion (along State Route 423) is one of the most

impressive memorials anywhere outside of Washington, D.C. The circular monument

of white Georgia marble, with simple Doric features and spacious grounds,

combine to make it another worthwhile diversion while in Marion.

A side trip to the impressive Harding Memorial is a worthwhile diversion on State Route 423 south of downtown Marion.

To resume your tour of the originally proclaimed 1913 route, find your way to

the Marion County Courthouse at the northeast corner of Center Street and Main

Street, and again reset your trip meter to zero. The centerpiece of downtown

Marion, the courthouse was completed in 1886 "for the good of the public," or

pro bono publico as inscribed above the impressive south entrance. Over the

years, the exterior has been cleaned and left intact, in conjunction with

downtown improvement efforts.

Unfortunately,

extensive alterations have mutilated the interior—with losses including an

original staircase, ornate woodwork, a large courtroom, and decorative murals.

Unfortunately,

extensive alterations have mutilated the interior—with losses including an

original staircase, ornate woodwork, a large courtroom, and decorative murals.

The Marion County Courthouse, restored only on the outside, is the centerpiece of downtown improvements in Marion.

From the courthouse, go west on Center Street, passing the fabulous neon sign of

the Palace Theater after just a few blocks. At 0.6 miles are the two busy

railroad crossings of Norfolk Southern and CSX Transporation, respectively.

Tucked neatly between the tracks is the restored Marion Union Station, which was

built to serve the four railroads that originally passed through the city.

Another set of tracks—a later generation of the parallel lines that previously

passed through Galion and Caledonia—is at the north side of the station.

A caboose and crossing tower at a restored Union Station are reminders of a rich Erie Railroad history in Marion.

If you are a rail fan, a stop at the station is a must. A handy book by the

publishers of Trains Magazine lists five "hot spots" in Ohio for watching

trains, and this is one of them. During my short visit, I met several men from

Ontario who were on their way to a large model railroad show in Cincinnati. Each

one of them had a camera strapped around his neck, mostly shooting pictures from

ground level, but sometimes climbing the old Erie crossing tower (just above a

restored Erie Lackawanna caboose) for a better vantage point. Marion is steeped

in Erie Railroad history, with the remains of a large yard and shops just west

of here.

Marion is also renowned for its history in the manufacture of heavy equipment

such as the steam shovel. Just west of the railroad crossings is an interesting

memorial, plus a historical marker which states that at its peak in the middle

of the twentieth century, the adjacent Marion Power Shovel plant employed about

2500 workers. Later in the century, the National Aeronautics and Space

Administration (NASA) selected the company "to build the crawlers that transport

spacecraft to their launch pads." Ironically, the operation was purchased by a

Bucyrus company, then closed. Marion had previously lost out to interests in

Bucyrus when the Lincoln Highway was relocated in 1913.

At 0.8 miles, angle right and follow State Route 309 out of town. More railroad

tracks will be crossed, and much of the old Erie complex—now occupied by

CSX—will be visible at your left. five miles ahead, the route passes through the

unincorporated crossroads town of Big Island, which serves as a community center

for Big Island township. The interesting name is attributed to early pioneers

who found a prominent island like grove of trees in the middle of the then wet

prairie.

At 8.7 miles, a repainted Mail Pouch barn is partially visible above the crops

growing at left. Then at 9.3 and 9.9 miles, curve improvements have rendered

short sections of bypassed roadways which remain as access roads. These are both

typical of highway improvements that commenced in 1930s, when the speeds of cars

and trucks significantly increased. Smooth curves were built to replace sharp

curves, and superelevation became more of a factor in holding vehicles to those

curves.

At the second curve, take note of the white-on-brown signs pointing to the

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. I have never visited this site, so I went online

to learn more about it—and it seems to be a good choice for a future adventure.

Operated by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, the area covers over 8,600

acres—just a fraction of the 30,000 acres that comprised the original prairie.

The site is "situated in a natural basin of flat, poorly drained soils formerly

covered by prairie sloughs," with large marshes, a greentree reservoir (that's a

new term to me), an upground reservoir, and 125 ponds of various sizes. Crops

and meadows are managed for nesting and migrating waterfowl, and plantings

provide permanent cover for upland wildlife.

This author has heard it said that before the pioneers starting clearing trees

from the Ohio lands, a squirrel could cross the state without touching the

ground. Considering the several prairies already encountered on this brief tour,

and with more still to come, it is a good bet that there wasn't much pioneer

squirrel traffic in the northwest part of the state. In some cases, the prairies

and swamps were so expansive that several adjacent sections of land could not be

monumented by the original government surveyors.

A half mile west of the directional signs for Killdeer Plains, slow down as you approach another unincorporated crossroads town. This is Meeker, which shows up as Cochrantown P.O. and Scott Town in the old county atlas. At 10.5 miles, angle left onto the town's modest Main Street, which features an old canopy gas station (now a popular tavern), a row of strikingly similar light colored houses, and a well-kept church property. For some reason, the NPS study did not inventory the old gas station in Meeker. I have a feeling that they mistakenly buzzed through town on the numbered road, not realizing that the 1913 route had a short diversion here. The same thing could probably be said for the several noteworthy sites back in photogenic Caledonia—none of which were listed in the inventory.

After passing through Meeker and curving right past an interesting old concrete

walled bridge, turn left at the stop sign and resume west with State Route 309.

This portion of the route follows the section lines of the rectangular survey

system for fifteen miles before bending to enter Kenton, the county seat of

Hardin County. The straightness—and resultant monotony—of this part of the

original 1913 route is reminiscent of the 45 mile Lincoln Highway straightaway

west of Upper Sandusky.

Having traveled this unremarkable part many times previous, this particular day

I decided to take a side trip into Hardin County's Amish Country. The

southeastern part of the county is home to about 1,000 Old Order Amish, and it

is not unusual to see a horse and buggy traveling the roads in this area. I paid

a visit to the Pfeiffer Station General Store and purchased that stick of beef

jerky that I didn't get in Caledonia. Two barefoot Amish boys were being treated

to ice cream cones courtesy of their big brother. Across the road from the

general store is Wheeler's Tavern, a beautiful brick structure that historians

believe

was

a stop on the Underground Railroad.

was

a stop on the Underground Railroad.

State Route 309 east of Kenton is a thoroughfare for horses and buggies making their way to town from Hardin County's large Amish community.

At 24.7 miles, just past the junction with County Road 144 (the return road from Pfeiffer Station), observe the extra wide paved berm which accommodates horse and buggy traffic. The Amish come to Kenton for shopping, and hitching posts are at several downtown locations. Another mile ahead is the original fringe of the city, with two old fashioned motels still in operation after fifty plus years, plus another canopy gas station. The NPS Study did inventory this fine specimen, plus an even finer one just east of downtown at 311 East Franklin Street.

Upon reaching the southwest corner of the prominent city block occupied by the

Hardin County Courthouse, reset your odometer to zero for the final time.

Constructed of Indiana limestone and opened in 1915, this is one of the newest

courthouses in Ohio's eighty eight counties, and one of my personal favorites.

The exterior is most attractive when decorated for the Christmas season, with colorful wreaths and bows, plus multiple strings of

lights which reach from the top corners of the building to the street corners

below.

Christmas season, with colorful wreaths and bows, plus multiple strings of

lights which reach from the top corners of the building to the street corners

below.

The Neo‑Classical Hardin County Courthouse is well‑situated on a block of high ground above the Scioto River in Kenton.

At the northeast corner of Franklin Street and Market Street—just one traffic

signal west of the previous courthouse corner—is a small greenspace which has

been set aside as Gene Autry Park. Westbound travelers may

have

to look over their right shoulders to see a colorful new mural painted to

commemorate the Kenton Hardware company. The mural depicts the famous movie and

television cowboy on his fine horse Champion. The Gene Autry cap pistol was

perhaps the most noted of the many Kenton toys.

have

to look over their right shoulders to see a colorful new mural painted to

commemorate the Kenton Hardware company. The mural depicts the famous movie and

television cowboy on his fine horse Champion. The Gene Autry cap pistol was

perhaps the most noted of the many Kenton toys.

This new mural in downtown Kenton is a tribute to the city's past role as a major toy producer, including the Gene Autry cap gun.

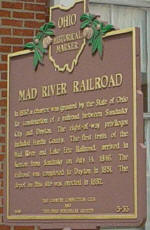

In the very next block is a restored brick depot which last served yet another

property of the New York Central Railroad. This line was chartered in 1832 as the Mad River and Lake

Erie Railroad, and was the longest part of a

York Central Railroad. This line was chartered in 1832 as the Mad River and Lake

Erie Railroad, and was the longest part of a

north-south

route across the state to the Ohio River.

north-south

route across the state to the Ohio River.

Ohio's second railroad, the Mad River and Lake Erie, is remembered in Kenton with a historical marker at this restored brick depot.

At 0.3 miles, the route angles right and leaves town on Lima Street. Beyond the

city, the suprisingly straight road follows a glacial moraine which is well

defined on geologic maps. South of the moraine was a great prairie known locally

as the Onion Swamp, and to the north was a similar prairie called the Hog Creek

Marsh. Now drained, these old wetlands contain some of the most fertile soil in

the state. In the 1830s, the original road was laid out as the Kenton and Kalida

State Road, but as settlers moved into the quarter sections near what is now Ada,

much of the diagonal route disappeared as roads were typically moved to follow

the squared lines of the government surveys. Along with the first several miles west of Kenton, other snippets of the old state road survive as diagonals

in Allen County and also in Putnam County—where the town of Kalida was the

original county seat.

miles west of Kenton, other snippets of the old state road survive as diagonals

in Allen County and also in Putnam County—where the town of Kalida was the

original county seat.

This freshly painted country church at the end of a long tangent on the old Kenton and Kalida State Road was visible for three miles in the morning sunlight.

At 4.2 miles, watch closely for a stained and nearly illegible cut stone column

erected on the right side of the road. The column was once part of the previous

courthouse in Kenton, and the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR)

salvaged many circular stones like this to mark the route of Hull's Trail

through the county. Fort McArthur, just south of here (and commemorated by a

marker in the courthouse square), was one of several encampments and stockades

established along the trail as General William Hull made his way north to

Detroit in the early stages of the War of 1812—a war which actually ended in

1814.

At 9.9 miles, an old roadside rest is one of the last remnants of the town of

Huntersville, which was platted in 1836. The Kenton and Kalida State Road was

kinked here to square up with the town's main east west street before resuming

northwesterly. That alignment existed until the 1930s, when a modest curve was

constructed. The land between the old main street and the new curve was then

purchased for the original rest area (the present structures probably came

later). The generous right of way that now exists from Kenton through

Huntersville was part of a major twelve mile improvement in the 1960s, when the

route was marked as 30 South. At the shelter house, an old black on white

"Huntersville" sign has been rendered illegible after years of exposure to the

elements.

At 11.9 miles, the route gently curves west to begin a straight fourteen mile path toward Lima. The straight path once again follows the square-mile lines of the rectangular survey system—a mere seven miles south of and parallel with the similarly straight final route of the Lincoln Highway.

At 13.1 miles, where State Route 235 drops south from Ada to join with State Route 309, the originally proclaimed route of the Lincoln Highway finally meets its first successor route. However, this successor route was like its predecessor in being short lived—in fact, the route was changed so frequently between 1913 and 1919 that this author has yet to find two guide books that describe the same path between Ada and Lima. However, there was enough reliable evidence from a December 1913 Lima newspaper article for this author to chart the first successor route in his road guide project.

If continuing on to Lima, tourists will note that for address purposes, the route is signed as Harding Highway in Allen County. As far as anyone knows, the only other places where the Harding Way or Harding Highway names survive are in Galion, as described in the opening paragraphs, and in Marion County. I don't recall seeing Harding Highway road name signs in Marion County, but it is labeled as such on the official county map. East of Lima, Harding Highway is built up with strip malls and franchise eateries, and is the busiest entrance to Lima from Interstate Route 75.

It is a good bet that many historians in Ohio would equate the Harding Highway with U.S. 30 South between Mansfield and Delphos, but trail maps of the 1920s show that the route actually crossed the entire state. One version of its trail markings was a black stylized Roman letter H within a black circle, all on a white diamond shaped sign. At the peak of its promotion, the highway was advertised as "a new transcontinental route between San Francisco and the major cities on the Atlantic Coast." A folder sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce in Burlington, Iowa extolled the virtues of a "shorter and better road between Pittsburgh and Denver." All of this was soon forgotten as people were conditioned to follow roads with numbers, and not roads with names.

At 26.5 miles, State Route 309 angles right to follow Bellefontaine Avenue into Lima. Stay with Bellefontaine Avenue (ignore a State Route 309 diversion which follows Elm Street) until it crosses a river bridge, angling left onto Market Street. The new Lima High School will be at the right. After crossing the railroad, watch for the location of the former Interurban Building (now home to the county health department) at 219 East Market Street (at right), and the old Lincoln Highway Garage (Roberts Building) at 120 East Market Street (at left).

This author helped prepare the text for a bicentennial historical marker that

was placed in front of the Interurban Building. Entitled "The Interurban Era,"

the marker commemorates Lima's role as a major hub in Ohio's extensive electric

railroad network. At its peak in 1916, Ohio had nearly 2,800 miles of interurban

lines—the most of any state and nearly twenty per cent of the national network.

Indiana was second, but fell short of Ohio's mileage by nearly a thousand miles.

No Ohio town of 10,000 people was without interurban service.

The Lincoln Highway Garage in Lima was at 120 East Market Street, near the city's Town Square, which was the original point of intersection of the Lincoln and Dixie Highways.

Lima's Town Square is the point of ending for this tour. Significantly, it was also the original point of intersection of the Lincoln Highway and the eastern branch of the Dixie Highway. In 1919, the U.S. Army—while planning their transcontinental convoy—insisted that the Lincoln Highway route be moved to its straight path west of Upper Sandusky. That revision moved the important intersection point to Beaverdam, which is now home to three major truck stops at the busy I-75/U.S. 30 interchange. Thus, Beaverdam is still today a legitimate candidate for any "Crossroads of America" boast on a billboard.

The originally proclaimed route of the Lincoln Highway actually continues on to Delphos, following State Route 309 to Elida before meandering all over the place to get there. This complicated route—which was used only until 1915—has also been previously charted in this author's road guide project. Hard copies of the materials are still available from the author.

With our journey now complete, we can look back on a rewarding adventure that truly had much to see in just seventy eight miles. The charted course passed through three county seats (Marion, Kenton, and Lima), plus another city (Galion) large enough to be one. Only one other town on the route (Caledonia) was large enough to be incorporated, but it certainly was a gem of a place—proving that sometimes, there can even be rewards in leaving the two lane highways. Many points of interest were in the urban locations, but rural areas—especially east of Marion—were highlighed by a good share of interesting old road remnants. There was a surprising number of informative historical markers, plus fine examples of early highway architecture such as motel courts and canopy gas stations—survivors from the earliest days of U.S. 30 South. Perhaps the only thing missing from a typical tour in Ohio's Lincoln Highway corridor was a roadway with brick! All in all, I consider it a day very well spent, and encourage readers to soon follow after my happy trails.